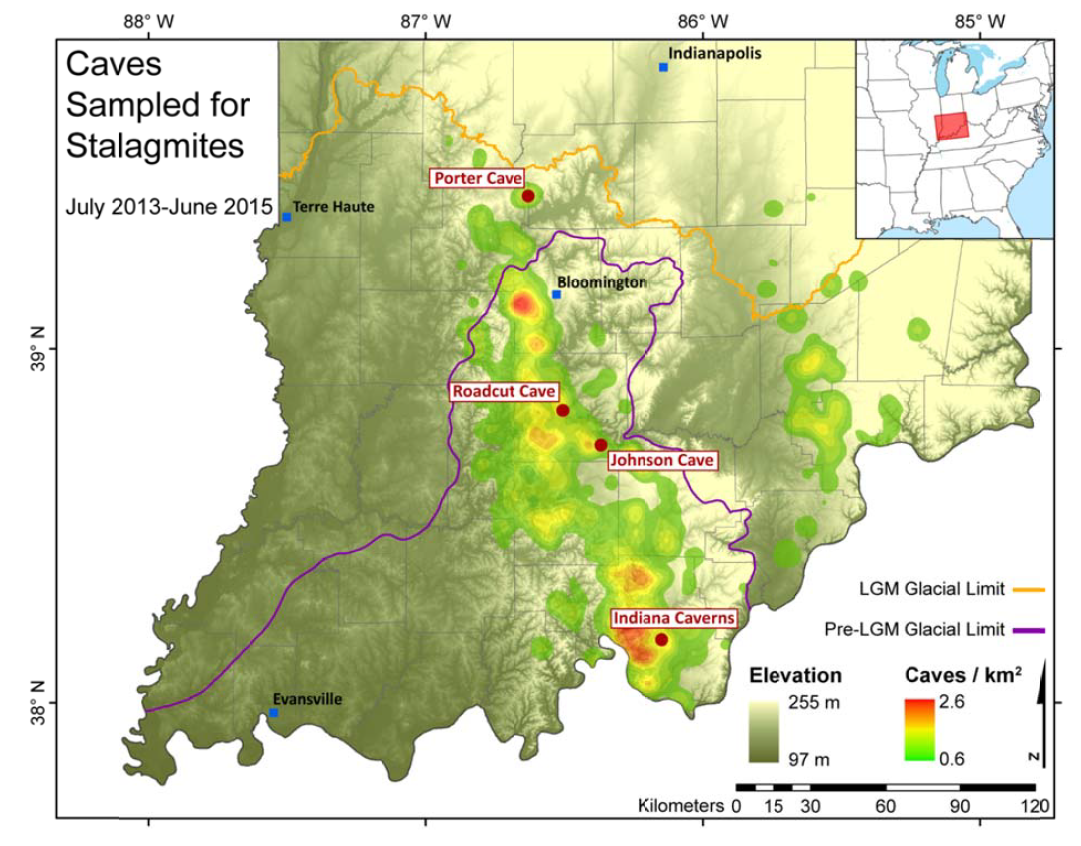

Southern Indiana’s numerous caves offer excellent opportunities for learning about climate and environmental changes in the eastern and central United States. For my doctoral research, I investigated this region’s paleoenvironmental history through samples taken in four caves in the Mitchell karst plateau: Porter Cave, Johnson Cave, Roadcut Cave, and Indiana Caverns (a portion of Binkley Cave).

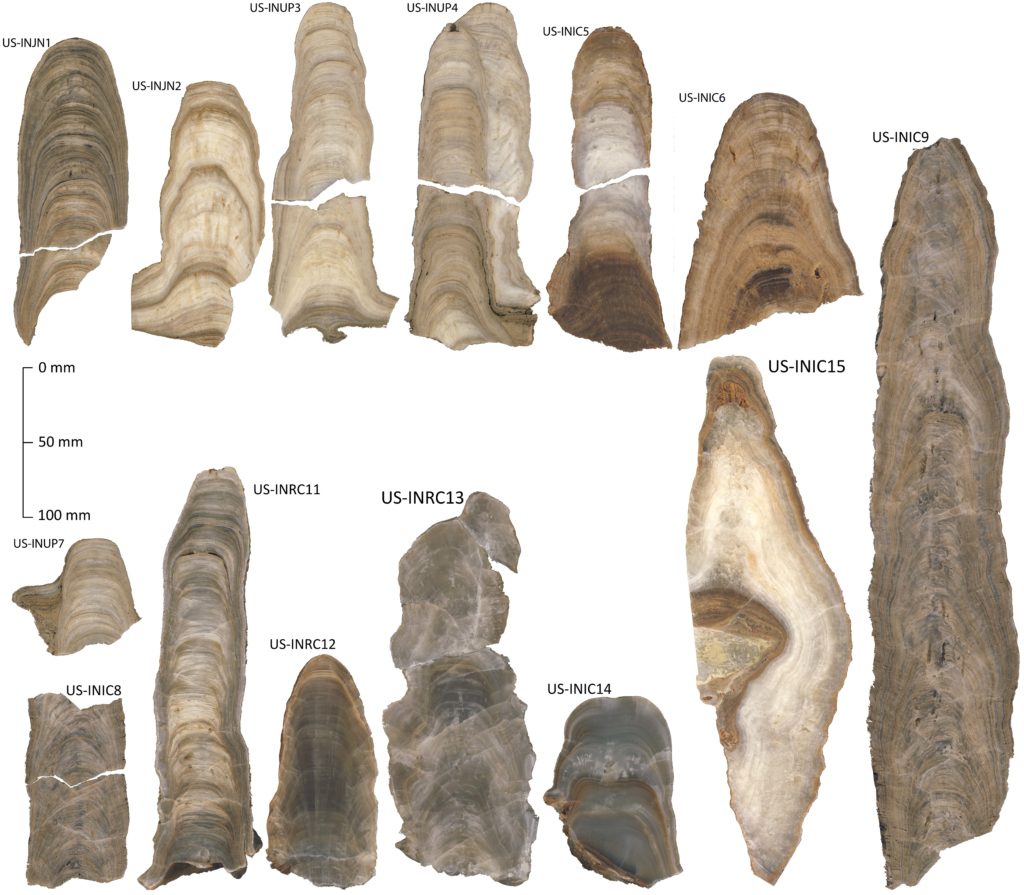

I collected a total of fifteen stalagmites with permission from these four caves from relatively inaccessible and rarely visited portions of the caves (due to concern for cave aesthetics and preservation). The suite of stalagmites varied wildly in color and general structure, in part due to different ages and different overlaying bedrock and soils.

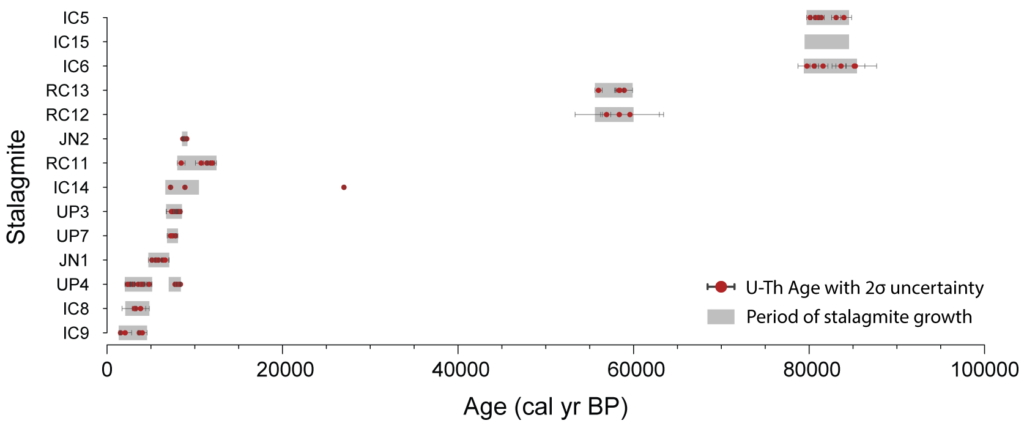

These stalagmites generally grew for brief (<5000 years) periods of time, and growth periods were clustered in only minor portions of the past 90,000 years. These stalagmites appear to have grown only in rare environmental conditions when temperatures are warm enough and wet enough to supply water to the cave systems, but not so wet as to prevent drip waters from getting saturated in calcium carbonate. The growth of the stalagmites during these ‘Goldilocks’ environmental conditions allows the growth phases of the stalagmites themselves to be used as a powerful paleoenvironmental proxy. For example, it appears that at least two periods in the last glacial period (55-60 ka and 78-85 ka) were similar enough to Holocene conditions to allow stalagmites to grow.

I also selected two Porter Cave stalagmites for a high-resolution analysis of environmental change during the Holocene (the current warm interglacial period). By combining 1000 stable isotope data with petrographic analysis, ultraviolet-stimulated luminescence imagery, and the phases of stalagmite growth and hiatus, I constructed a new record of climate change for southern Indiana. The results suggest that several multi-centennial periods of very dry conditions were present in southern Indiana between 2000 and 5000 years ago. Rather than the consistent aridity found in the Great Plains and mid-continent at this time, southern Indiana appears to be located near a steep precipitation gradient and frequently returned to very wet conditions during this period.

While high-resolution analysis focused on the two previously mentioned stalagmites, great potential remains for the stalagmites taken from the remaining caves. Stalagmites from Roadcut Cave offer a record of two periods of time not recorded in the other caves, with a particularly intriguing record dating to the end of the Younger Dryas period and transition into the early Holocene. Three stalagmites from Indiana Caverns appear to capture a brief growth phase that occurred during a warm Greenland Interstadial/Dansgaard-Oeschger event. Stalagmite growth in Johnson Cave appears to be anti-phase to the Porter Cave stalagmites, and further analysis may help decipher what environmental conditions are triggering these growth/hiatus phase changes. Future research projects examining these stalagmites and other records in more detail can greatly add to our understanding of millennial climate change in the American Midwest.

This research was supported by National Science Foundation Grant #BCS-1433904.